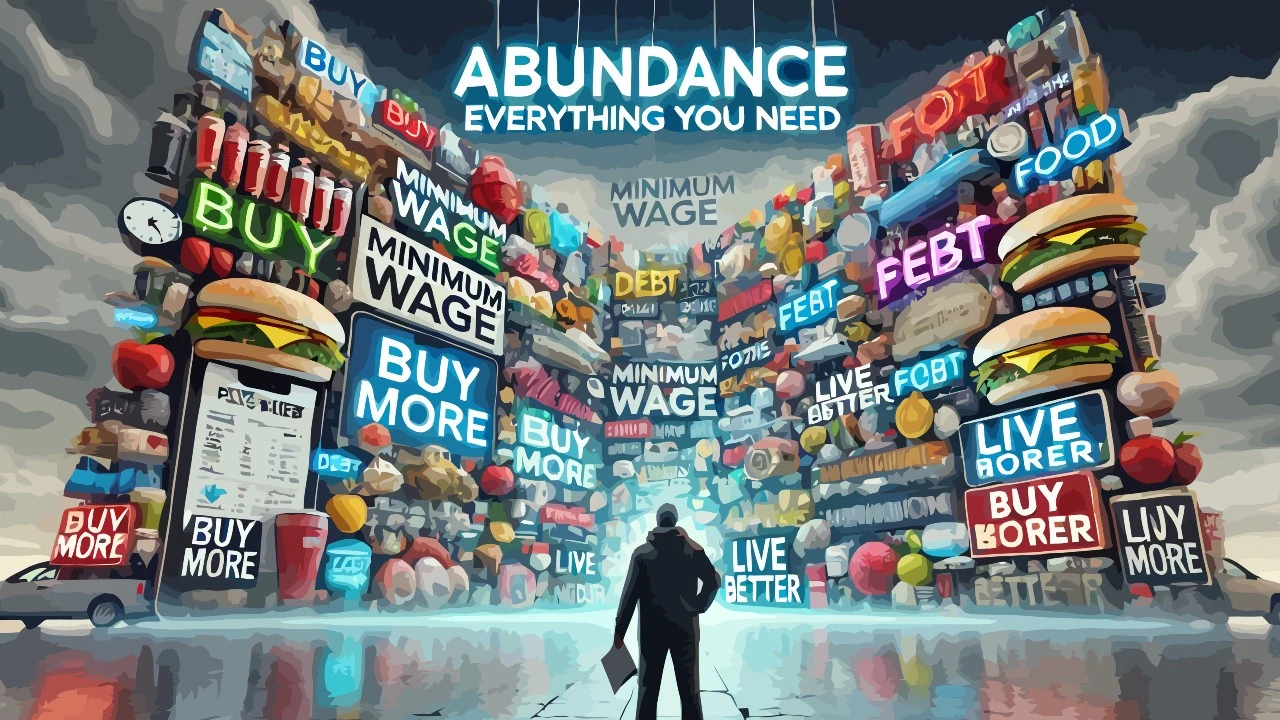

Italy is often described as an impoverished country, marked by precariousness, stagnant wages and rising costs. Yet, at the same time, everything seems to be in motion: full shopping malls, booked holidays, new phones and cars on the road. How do you reconcile these two realities?

This article analyses the gap between real economic conditions and collective behaviour, highlighting a social model based on easy credit, pressure to conform and denial of the problem.

Contents

#1. Stagnant wages: data vs perception

Over the past thirty years, real wages in Italy have stagnated almost completely. According to the OECD, between 1990 and 2022, the average real wage in Italy grew by only 2.9%, while in Germany it increased by 33% and in France by 31%. This figure takes inflation into account and is therefore a direct measure of effective purchasing power. Added to this picture is an increasingly fragile work environment: 22% of contracts activated in 2023 are fixed-term, with an average duration of just 3.5 months.

According to ISTAT data, in 2023 over 3 million Italian workers were classifiable as “poor despite working”, that is, they received an income from work lower than the relative poverty threshold. Furthermore, according to Eurostat, 25.4% of the Italian population is at risk of poverty or social exclusion, one of the highest percentages in Western Europe.

However, these data seem to be contradicted by what we observe every day. Cities are animated, traffic is heavy, restaurants are booked in advance and holidays have become an indispensable normality. This dissonance between indicators and appearances is not just a question of perception: it has structural and economic roots. To understand it, we need to look beyond income and analyze how consumption is actually supported.

#2. Growing consumption: driver of debt

In a context of stagnant wages, the only way to support consumption is to resort to debt. And in fact, according to data from the Bank of Italy, consumer credit reached 134 billion euros in 2023, with an annual increase of 6.5%. This item includes personal loans, installment payments for the purchase of goods and services, revolving cards and deferred payment formulas offered by large e-commerce operators. Debt has become an integral part of daily spending.

A 2023 Crif report indicates that 37% of Italians between 25 and 45 have at least one active loan, with an average duration of 48 months. Over 20% of these loans concern non-essential goods (electronics, holidays, furniture). Furthermore, “facilitated” installment payment methods (often interest-free) are now also offered for expenses under 100 euros, helping to make the use of debt a normalized behavior.

According to an Ipsos study, over 45% of Italians have used installment payments at least once for everyday goods. This data shows how the boundary between consumption and debt is increasingly blurred. What once required reflection or planning is now accessible without hesitation. Digital platforms have integrated credit into the purchasing process, transforming it into an automatic and socially neutral option.

The danger lies in the illusion of stability: as long as the installment is low, everything seems sustainable. But with the increase in interest rates decided by the European Central Bank in 2023 (up to 4.5%), many families risk not being able to meet the deadlines, triggering insolvencies and financial tensions in a chain reaction.

👉 Read also: Principles of Economics and World Orders, by Ray Dalio

#3. Social pressure and imitation

Consumption, today more than ever, is also a symbolic act. It serves to signal belonging, success, normality. We do not consume only out of need, but to avoid feeling excluded. In an era in which visibility is central, the idea of ”living like others” becomes an implicit imperative. Social pressure is not explicit, but acts through the repetition of models, images, expectations.

The Censis 2023 Report describes a “society of representation” in which the coherence between economic possibilities and lifestyle is less important than the coherence between image and context. 33% of Italians say they make purchases “to feel aligned with others”. This phenomenon is accentuated among young people, but extends across all social classes.

Conspicuous consumption on social media, hostility towards personal austerity, the fashion for “experience” as an inalienable right create an environment that is difficult to escape. Not participating becomes a declaration of failure or marginalization. According to the Pew Research Center, more than half of young Europeans say they feel inadequate when faced with what they see on social networks.

The consequence is a psychological automatism: if everyone travels, I have to do it too. If everyone changes cars every five years, I can’t stay behind. But these automatisms are not based on solid economic foundations. They are cultural scaffolding supported by credit, compromises and invisible sacrifices, which in the long run generate frustration and instability.

#4. Collective denial and role of media

Why doesn’t this system collapse? A key part of the answer is collective denial. Citizens know, rationally, that the situation is unsustainable. But they choose, emotionally and socially, to ignore it. Denial is a psychological defense mechanism, but also a cultural adaptation.

Traditional media rarely address the issue of the economic sustainability of consumption in a systemic way. Instead, they celebrate the recovery in consumption, extol record car sales, and describe holidays and lifestyle as indicators of success. According to Nielsen data, in 2023 advertising investments in Italy increased by 2.9%, with a 5.4% increase in the travel, luxury and technology sectors. The narrative is: “Everything is fine, so spend”.

At the same time, online content offers a filtered, glossy, seamless reality. According to ISTAT, in 2022 over 65% of Italians declared themselves satisfied with their lifestyle, while only 39% considered their income adequate. This disconnect between perception and condition is a symptom of a culture that rejects the idea of degrowth, sobriety or limit.

Even the institutions do not question the model: bonuses, incentives, consumer financing are tools that keep the economic machine alive. But without a structural change, the risk is that denial becomes a social bubble, ready to explode at the first shock.

#5. A two-speed society

The final effect of this system is social polarization. On the one hand, those who have the means, savings, family assets or access to credit can continue to consume without difficulty. On the other hand, those who do not have these resources go into debt so as not to be excluded or silently exclude themselves. This creates a two-speed society, not only economic but cultural.

Eurostat reports that in Italy the household savings rate fell to 8.7% in 2023, against a European average of 13.2%. Low-income households save less than 2%, while those with high incomes save more than 15%. This divergence puts social cohesion at risk: in the event of a crisis, only a portion of the population will have the tools to react.

The system holds as long as conditions remain stable. But external events such as an energy crisis, a tax hike, a credit squeeze are enough to disrupt the equilibrium. The result can be a wave of insolvencies, a sudden drop in consumption, social protests or even a general crisis of confidence.

As French economist Thomas Piketty wrote:

A society that grows only in consumption, but not in income, is an unstable and fragile society.

And just as in financial markets, in social systems too much trust in automation leads to a crisis when least expected.

Leave a Reply