Over the last century, major world currencies have undergone significant devaluations, profoundly affecting citizens’ purchasing power. Inflation, economic crises and political choices have contributed to reducing the real value of money, leading to a growing gap between nominal and real value.

This article analyses the phenomenon by comparing six major currencies, including the Italian lira and the euro, examining the evolution of purchasing power with respect to consumer goods and gold.

Disclaimer:

The information provided does not constitute a solicitation for the placement of personal savings. The use of the data and information contained as support for personal investment operations is at the complete risk of the reader.

Contents

- The Italian lira – Reconstruction and decline

- The euro – Stability and discontent

- The US dollar – From gold to fiat

- The British pound – The Decline of the Empire

- The Japanese yen – Growth and deflation

- The German mark – From Weimar to the euro

- The Zimbabwe dollar – An economicide

- Only one currency never devalues

| Currency | Period analyzed | Initial gold value (per ounce) | Final gold value (per ounce) | Devaluation factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italian Lira | 1950-2001 | £38,000 | £500,000 | ~13x |

| Euro | 2002-2024 | €300 | €1,800 | ~6x |

| US Dollar | 1920-2024 | $20.67 | $2,000 | ~97x |

| British Pound | 1950-2024 | 12 £ | £1,500 | ~125x |

| JPY | 1970-2024 | 5,000 yen | 300,000 yen | ~60x |

| German Mark | 1921-2002 | 1 mark (Weimar) | Hyperinflation (uncountable) | Hyperinflation (uncountable) |

| Zimbabwe Dollar | 2000-2009 | 13,000 ZWD | Hyperinflation (uncountable) | Hyperinflation (uncountable) |

#1. The Italian lira

Reconstruction and decline

The Italian lira has lived through a turbulent century, marked by world wars, economic reconstruction and recurring crises. After the Second World War, inflation hit Italy hard, drastically reducing the purchasing power of the lira. In the 1970s and 1980s, galloping inflation pushed prices skyrocketing: a coffee that cost 100 lire in 1950 but reached over 1,000 lire in the 1990s.

Compared to gold, the devaluation was even more evident: in 1950, an ounce of gold was worth about 38,000 lire, while in 2001, on the eve of the introduction of the euro, the price exceeded 500,000 lire. The lira has witnessed a series of forced devaluations also due to the monetary policies adopted to support national industry, often at the expense of monetary stability. The public debt crisis in the 1980s further aggravated the situation, leading to high interest rates and growing international distrust.

The continued loss of value finally pushed the Italian government to join the project of the single European currency, with the hope of stabilizing the national economy. However, the transition to the euro did not completely eliminate the structural fragilities of the Italian economy, which continued to suffer from low growth and high unemployment. The lira remains today a symbol of an era marked by profound economic and social changes.

- Above, a 500,000 lire banknote from 1997.

- Below, a 5 lire banknote from 1944.

#2. The euro

Stability and discontent

The introduction of the euro in 2002 promised stability and economic integration. However, the 2008 financial crisis and tensions in European markets weakened the single currency. Although inflation remained moderate compared to other currencies, the euro lost purchasing power against gold and some consumer goods. In 2002, an ounce of gold was worth about 300 euros; today it is worth more than 1,800 euros. At the same time, the price of everyday goods, such as bread and fuel, has increased significantly.

The 2010 sovereign debt crisis has further challenged the stability of the euro, exposing the fragilities of the weakest countries in the eurozone. Austerity policies and financial bailouts have contributed to slowing economic growth, leaving many economies vulnerable. Furthermore, recent global inflationary pressures have highlighted that even the euro is not immune to market pressures, reopening the debate on the need for more flexible fiscal policies.

#3. The US dollar

From gold to fiat

The U.S. dollar has undergone one of the most studied devaluations in the world. Since 1971, with the abandonment of the Gold Standard, the dollar has become a fiat currency, subject to inflation. In 1920, one dollar could buy about 1.5 grams of gold; today, it costs over 60 dollars for a single gram. Consumer goods have also followed a similar trend: a bottle of milk cost a few cents in the 1920s, while today the price exceeds 3 dollars.

The dollar’s influence as the world’s reserve currency has allowed the United States to finance public deficits without suffering the same inflationary pressures as other economies. However, the economic crises of 2008 and 2020 have highlighted the vulnerabilities of the American currency. The adoption of quantitative easing policies has increased the money supply in circulation, pushing many investors to seek refuge in assets such as gold and cryptocurrencies.

Rising geopolitical tension and trade wars have also weakened the dollar’s position in international markets. Although it remains the world’s most traded currency, its domestic purchasing power continues to decline, fueling debate over the future of the global financial system.

- Above, a 1 USD banknote convertible into silver before 1971.

- Below, a 1 USD banknote not convertible into silver after 1971.

#4. The British pound

The decline of the empire

Once a symbol of global economic power, the British pound has gradually weakened over the course of the 20th century. From the collapse of the British Empire to the crisis of 2008, the pound has lost much of its purchasing power. In the 1950s, an ounce of gold cost about 12 pounds; today, the price is more than 1,500 pounds. Housing and food costs have also followed an inflationary trajectory.

The oil crisis of the 1970s and the economic reforms of the 1980s profoundly transformed the British economy, but they were not enough to stop the devaluation of the pound. The Brexit referendum of 2016 further destabilized the currency, causing strong fluctuations on international markets.

Today, the pound remains a strong currency, but its global influence is significantly reduced compared to the days of the British Empire. Current economic challenges, including inflation and the energy crisis, raise questions about its future.

#5. The Japanese yen

Growth and deflation

After World War II, Japan experienced rapid economic growth, but also periods of inflation and deflation. The yen suffered significant devaluations during the real estate crisis of the 1990s, but remained relatively stable in the years that followed. In 1970, an ounce of gold was worth about 5,000 yen; today it is more than 300,000 yen.

The Bank of Japan’s expansionary monetary policy has helped keep interest rates low, but it has also created long-term structural problems. The phenomenon of deflation, which has affected Japan for decades, has reduced economic growth and increased public debt.

In recent years, global inflationary pressures have rekindled debates about the need for structural reforms and a possible review of monetary policies. However, the yen continues to be considered a safe haven currency in times of international crisis.

#6. The German mark

From Weimar to the euro

The German mark has experienced two very different historical phases: the hyperinflation of the Weimar Republic and the stability of the post-war period. After the First World War, Germany faced one of the worst inflationary crises in history. Between 1921 and 1923, the mark lost virtually all of its value. The price of essential goods, such as bread, went from a few marks to billions of marks. The main causes were the war reparations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles and the uncontrolled printing of money.

Hyperinflation destroyed the savings of the middle class and led to deep social tensions, contributing to the political instability of the period. The monetary reform of 1924, with the introduction of the Rentenmark, ended the crisis, but its consequences were felt for decades.

After World War II, West Germany introduced the Deutsche Mark, which became synonymous with economic stability and growth. The German Central Bank adopted tight monetary policies to avoid new inflationary crises. However, with German reunification and integration into the European Union, the mark was replaced by the euro in 2002.

Despite its demise, the mark remains a symbol of German economic resilience. The Weimar hyperinflation continues to be studied as an extreme example of the devastating effects of uncontrolled currency devaluation.

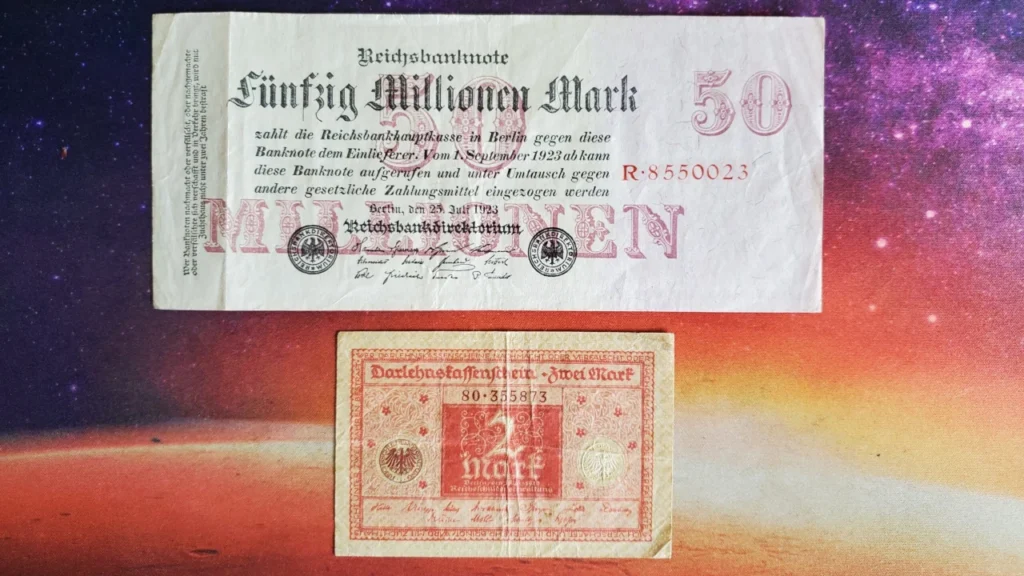

- Above, a 50 million mark banknote from 1923.

- Below, a 2 mark banknote from 1920 (just 3 years earlier).

#7. The Zimbabwe dollar

An economicide

The devaluation of the Zimbabwe dollar is one of the most dramatic examples of hyperinflation in modern history. It began in the early 2000s, when a combination of poor economic policies, political instability and international sanctions destabilized the country’s economy. The agricultural crisis, triggered by the controversial land reform of 2000, drastically reduced food production and exports, key pillars of the Zimbabwean economy.

Faced with falling production and rising unemployment, the government responded by printing large amounts of money to finance public spending. This led to an uncontrollable inflationary spiral. In 2008, inflation reached surreal levels: it is estimated that it exceeded 79.6 billion on an annual basis. Prices doubled every few hours and money quickly lost all real value.

Banknotes became symbols of this economic madness: up to 100 trillion Zimbabwean dollars were printed in denominations , but this was not enough to buy basic necessities. People resorted to barter or used foreign currencies such as the US dollar and the South African rand for everyday transactions.

In 2009, the government was forced to abandon the Zimbabwean dollar, legalizing the use of foreign currencies. Hyperinflation ended, but the social and economic consequences were devastating: millions of people lost their life savings, pensions became worthless, and confidence in the national currency collapsed.

The case of Zimbabwe remains a warning of the disastrous effects that irresponsible fiscal policies, corruption and lack of institutional trust can have on an economic system. Although the Zimbabwe dollar was reintroduced in 2019, popular distrust and economic hardship persist, leaving open the question of its future stability.

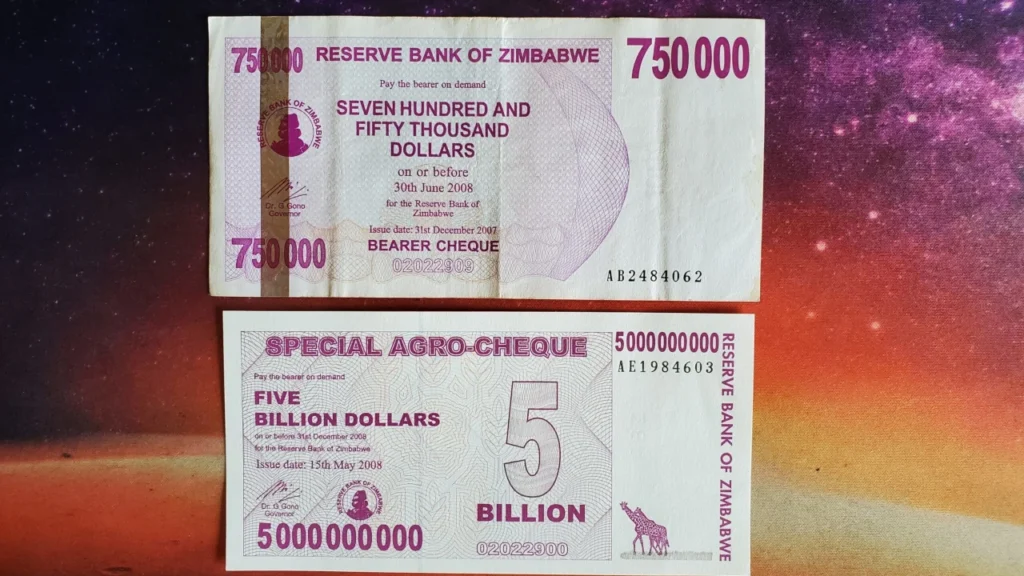

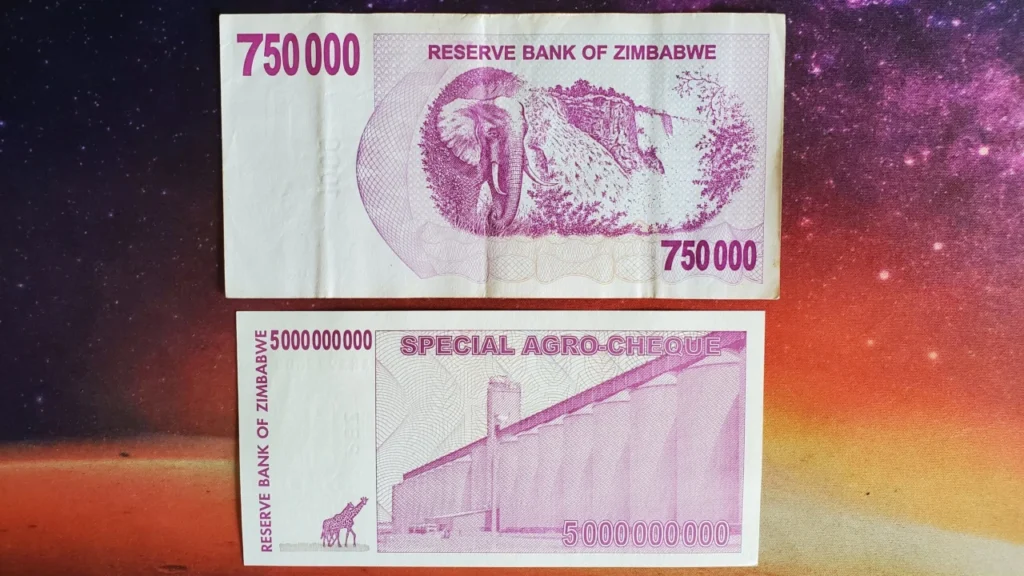

- Above, a 2008 $750,000 bill.

- Below, a $5,000,000,000 bill from 2008 (the same year!).

#8. Only one currency never devalues

Even though only a few of the major devaluations and inflations that have occurred (and continue to occur) throughout history have been mentioned, I think one concept is quite clear:

Any coin or currency over time loses value or dies.

Keeping a large amount of your savings in local currency, even cash, means exposing yourself to the constant risk of seeing its value silently deteriorate.

The only currency that has never lost its value, since its birth, and which has represented over the millennia the best way to protect (and sometimes even increase!) one’s purchasing power is just one: gold.

Let’s now see how the purchasing power of this currency has evolved over time:

| Year | Price in currency | What you can buy |

|---|---|---|

| 1886 | 20 lire | 20 kg of bread |

| 2024 | 400-450 euros (thanks to the 5.8 g of gold contained) | 100 kg of bread, mid-range cell phone, short vacation at a low price |

Even though almost 150 years have passed since the issue of this coin, its purchasing power has remained unchanged… in fact, it has even increased in this case! All thanks to one factor: the gold contained within it.

Leave a Reply