The economic history of Italy is closely linked to the evolution of its currency, from the lira to the euro. Analyzing the relationship between these currencies and the price of gold allows us to understand the mechanisms of monetary devaluation and their impact on purchasing power. Gold, always considered a safe haven, represents a key parameter for evaluating economic stability and the solidity of currencies.

This article explores the performance of the Italian lira and the euro in relation to the price of gold, highlighting how economic dynamics and financial crises have influenced the loss of value of the currency.

Disclaimer:

The information provided does not constitute a solicitation for the placement of personal savings. The use of the data and information contained as support for personal investment operations is at the complete risk of the reader.

#1. Italian lira: inflation and devaluation

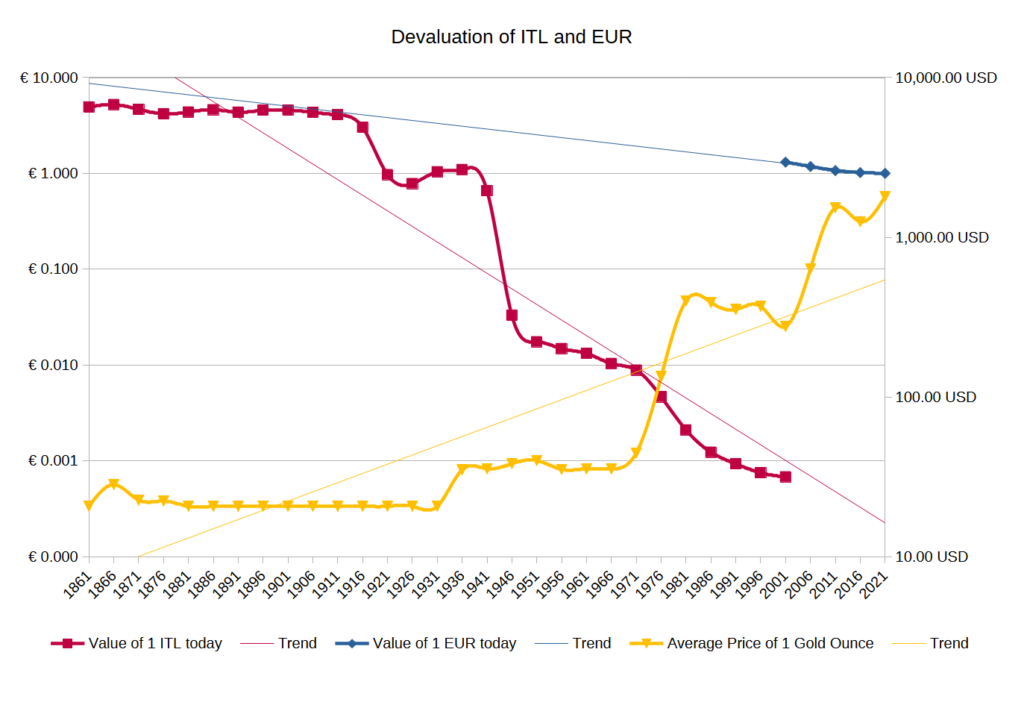

The Italian lira, introduced in 1861 as the official currency of the Kingdom of Italy, has gone through phases of stability and periods of strong inflation, with a devaluation that characterized much of the twentieth century. During the First World War, war spending caused a surge in public debt and an increase in inflation, laying the foundations for subsequent economic crises. In the 1920s, the lira underwent its first strong depreciation that led to the so-called “quota 90” desired by Benito Mussolini, an attempt at artificial revaluation of the currency that, however, did not resolve the structural fragilities of the Italian economy.

The Second World War marked another turning point. The destruction of infrastructure, occupation and military spending caused an economic collapse that led to a further collapse in the value of the lira. The post-war period was characterized by galloping inflation that drastically reduced purchasing power. However, with the Marshall Plan and entry into the OECD, Italy experienced a period of unprecedented economic growth between the 1950s and 1960s, the so-called “Italian economic miracle”.

Despite economic growth, inflation remained a chronic problem. The oil crises of 1973 and 1979 had a devastating impact on the Italian economy, increasing the cost of raw materials and triggering further waves of inflation. During this period, the price of gold became a key indicator of the devaluation of the lira. While in the 1950s an ounce of gold was purchased for around 38,000 lire, in the 1980s the price exceeded 200,000 lire.

In the 1980s, Italy’s economic management was marked by growing public debt. Government debt exceeded 100% of GDP, and inflation reached significant peaks, reaching 20% per year in some periods. The introduction of the EMS (European Monetary System) in the 1980s aimed to stabilize European currencies, but the lira was often subject to devaluations to maintain the competitiveness of Italian exports.

In 1992, financial speculation hit the lira hard, forcing Italy to temporarily exit the EMS after the famous Black Wednesday, when George Soros bet against the Italian currency. This crisis accelerated the process of economic reform that led Italy to adopt the euro. On the eve of the conversion in 2002, the lira had lost much of its original value: an ounce of gold, which in 1950 was worth 38,000 lira, in 2001 exceeded 500,000 lira.

#2. Euro: the challenge for stability

The introduction of the euro in 2002 was seen as a turning point for Italy and other Eurozone member countries. The aim was to create a stable currency, reduce currency fluctuations and strengthen European economic integration. The Maastricht criteria , which governed entry into the euro, imposed strict economic parameters, including a limit of 3% of GDP on public deficit and controlled inflation.

The first years of the euro were relatively stable, with low inflation and growing trade between member countries. However, the euro was quickly perceived by citizens as causing higher consumer prices, even though official statistics indicated modest inflation. This phenomenon, known as “perceived inflation”, generated widespread discontent, especially in Mediterranean countries such as Italy, Spain and Greece.

The global financial crisis of 2008 radically changed the scenario. The fall of Lehman Brothers and the collapse of the markets led to a deep recession that hit the Eurozone hard. The most indebted countries, including Italy, suffered an increase in the spread (the difference between Italian and German government bonds), signaling a loss of confidence in the markets. Gold, as often happens in times of crisis, became a safe haven: the price of an ounce went from around 300 euros in 2002 to over 1,200 euros in 2012.

The sovereign debt crisis of 2010 hit Greece in particular, but Italy also suffered the consequences. The austerity policies imposed by the EU fueled the recession, while unemployment rose and public debt continued to rise. The European Central Bank, led by Mario Draghi, intervened with extraordinary measures, including the famous “Whatever it takes” of 2012, which helped stabilize the markets.

In the years since, the euro has faced new challenges, including Brexit, international trade tensions and the COVID-19 “pandemic” . The latter has had a devastating impact on the European economy, pushing governments into unprecedented expansionary fiscal policies. The price of gold has reached new all-time highs, exceeding 1,800 euros per ounce in 2020.

The euro, while maintaining a certain stability against other global currencies, has shown signs of vulnerability in times of crisis. Economic divergences between member countries and difficulties in adopting common fiscal policies continue to pose a challenge to the stability of the single currency.

#3. Chart and table

I have created a graph and a table to make it easier to see the extent of the devaluation that the Italian lira has undergone, while the price of gold has continuously risen. Note how the greatest variations are highlighted in periods of war or economic crisis.

Sources and data:

Leave a Reply