Byzantine gold coins represent one of the most enduring symbols of the power and sophistication of the Byzantine Empire. These small masterpieces were not only instruments of economic exchange, but true witnesses to the culture, religion and politics of one of the longest-lived empires in history. Their charm lies not only in the gold that composed them, but also in the stories they contain: of ambitious emperors, of flourishing trade and of civilizations that intertwine along the routes of the Mediterranean.

In this article we will explore the world of Byzantine gold coins, starting from the origins of the Byzantine Empire itself to the decline of its monetary economy. A journey through centuries of history, in which gold shone not only as a symbol of wealth, but also of power and faith.

Contents

#1. Why I wrote this article

Reaching the hundredth article on this blog is not just a matter of numbers, but a real milestone for this blog. After months spent restructuring the contents, eliminating obsolete or irrelevant texts and integrating those still valid in a more refined form, I felt the need to celebrate this moment with something significant.

The contained cent arrives by chance right after having purchased a Histamenon of Constantine X , a gold coin of the Byzantine Empire that perfectly represents the essence of this space: a journey through eras, stories and objects that carry with them the weight of time and, thanks to the latter, the value of goods. It was not a simple purchase, but a gesture that embodies the search for authentic value, just like the path that guided the renewal of the contents of this space.

This article is therefore the symbol of a work that aims to make Mondiversi a more solid, curated and coherent space, without losing sight of the passion for what it tells. A new starting point to continue exploring, with an even more attentive and profound look.

#2. The Byzantine Empire: rise and fall

The Byzantine Empire, the direct heir of the Eastern Roman Empire, was officially born in 330 AD, when Emperor Constantine I refounded the city of Byzantium, renaming it Constantinople (present-day Istanbul). This new capital became the hub of an empire that, while maintaining Roman structures, developed with a strong Greco-Christian identity.

Over the centuries, the Byzantine Empire managed to survive the barbarian invasions that overwhelmed the Western Roman Empire, keeping classical culture alive and acting as a bridge between antiquity and the Middle Ages. The Empire’s golden age was reached under the reign of Justinian I (527-565), who attempted to reconquer lost western territories and promoted large-scale public works, such as the magnificent Hagia Sophia.

Constantinople’s strategic position, between Europe and Asia, granted the Empire control over the main trade routes. This economic advantage contributed to the Empire’s prosperity and favored the spread of Byzantine culture, which profoundly influenced neighboring civilizations.

However, the Empire faced constant problems: foreign invasions, economic crises and internal strife. The Crusades, initially seen as allies, turned into a threat when, in 1204, Constantinople was sacked during the Fourth Crusade. Despite a brief revival under the Palaeologus dynasty, the Empire never regained its former power and wealth.

The final blow came in 1453, when the Ottoman Turks, led by Mehmet II, conquered Constantinople. With the fall of the city, the thousand-year history of the Byzantine Empire ended definitively, but its legacy, especially through its gold coins, continued to shine in the centuries that followed.

#3. The origins of Byzantine coins

The Byzantine monetary tradition began in the footsteps of ancient Rome. However, already in the first decades, the Empire developed its own monetary identity. With the reform of Constantine I, the solidus was born, the gold coin that would become the mainstay of the Byzantine economy for centuries.

The solidus was not only an economic instrument: its intrinsic value and the purity of gold made it a stable and recognized currency throughout the Mediterranean basin, becoming the reference currency also for foreign peoples and kingdoms.

Early Byzantine coins continued to depict emperors in military or ceremonial attire, but over time the images were enriched with Christian symbols, reflecting the profound influence of faith on the Empire. Depictions of Christ Pantocrator and the Virgin Mary began to appear on coins, transforming them into not only economic but also spiritual objects.

The economic stability guaranteed by the solidus allowed the Empire to maintain control over vast territories and to influence the economies of neighboring countries. Trade flourished, and Byzantine coins became the preferred medium of exchange for merchants throughout the Mediterranean.

However, the expansion of the Empire and the continuous wars led to an increase in military and administrative expenses, leading, in the following centuries, to a gradual erosion of monetary stability.

#4. The Solidus: the coin par excellence

The Byzantine solidus (root of today’s italian term soldo), introduced by Constantine I in the 4th century AD, quickly became one of the most influential economic instruments of antiquity. Weighing approximately 4.5 grams of 95-98% pure gold, the solidus was distinguished by its extraordinary purity and reliability, qualities that earned it widespread distribution throughout the known world.

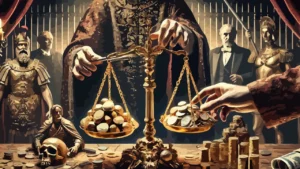

The solidus was not only a medium of exchange but also a powerful symbol of imperial authority. Its depictions varied depending on the emperor in power, but followed a recurring pattern: on the obverse, the bust of the emperor in ceremonial robes, often with the globus cruciger or the cross; on the reverse, sacred images such as Christ Pantocrator, the Virgin Mary or patron saints.

This iconographic choice reinforced the idea of imperial power as desired by God, underlining the fusion between political and religious power. The coin itself thus became an instrument of propaganda as well as trade.

The Byzantine solidus also found great success outside the imperial borders. European, Arab and Persian merchants used it extensively in international trade, recognizing its high intrinsic value. In many areas, the solidus was so appreciated that it was imitated by other states, although with varying results.

During the golden ages of the Empire, the economic stability supported by the solidus contributed to the financing of public works, military expansion and cultural diffusion. However, with the political decline and economic crises that hit the Empire from the 9th century onwards, the solidus also began to suffer devaluations and reductions in purity.

Despite this, its legacy endured: the solidus influenced the minting of many medieval European coins and remains one of the finest examples of stable and enduring coinage in history.

#5. Evolution of Byzantine coins

Byzantine coins, in addition to their economic role, were instruments of political and religious communication. Over the centuries, their symbolism was enriched, reflecting the cultural and spiritual changes of the Empire. Each coin was not only a means of exchange, but also a vehicle of propaganda, with images and inscriptions that conveyed messages of power, faith and legitimacy.

The first coins continued the Roman aesthetic, but soon adopted Christian symbols such as crosses, angels and saints. By the time of Justinian I, Christ Pantocrator began to appear frequently, representing the unity of Church and State. This link between religion and politics was one of the distinctive elements of Byzantine coinage.

Inscriptions also played a key role: imperial titles, invocations to God and messages of military victory were engraved on coins to reinforce the image of the emperor as a ruler chosen by God.

One of the most significant developments in Byzantine coinage was the introduction of the histamenon in the 10th century, during the reign of Emperor Nicephorus II Phokas (963-969). The histamenon began as a thinner and wider version of the traditional solidus, with a similar weight but a more flattened appearance. Later, under the reign of Basil II (976-1025), the histamenon took on a slightly concave shape, a feature that made it easily recognizable.

The histamenon was used in parallel with the tetarteron, a gold coin minted with a slightly lighter weight, probably introduced to facilitate internal payments and fiscal needs. This monetary duality generated a certain complexity in the Byzantine economic system, but also reflected the Empire’s adaptability to different commercial and fiscal needs.

The depictions on the histamenon continued to reflect the strong religious symbolism of the Empire. Christ Pantocrator remained a major subject, accompanied by imperial effigies and Christian symbols such as crosses and angels. Concave coins offered Byzantine minters the opportunity to experiment with new artistic techniques, creating more detailed and complex images.

The coexistence of histamenon and tetarteron continued until the beginning of the 12th century, when the economic crisis and devaluation led to changes in the monetary system. However, the histamenon remained one of the most representative symbols of Byzantine coinage and testifies to the Empire’s ability to adapt to the economic and political changes of the time.

Byzantine coins, therefore, were never simple commercial objects, but true instruments of power and cultural identity, capable of transmitting messages that went beyond the borders of the Empire itself.

#6. The decline of Byzantine coinage

The decline of Byzantine coinage was a direct reflection of the economic and political difficulties that afflicted the Empire in its last centuries of life. If the solidus had guaranteed stability and confidence in the markets for centuries, from the 9th century onwards internal tensions and continuous wars began to compromise the purity and value of gold coins.

Constant military campaigns, Arab invasions, wars against the Bulgarians and the Crusades generated enormous expenses that put a strain on the imperial coffers. Faced with these financial pressures, the emperors were often forced to reduce the amount of gold in the coins or to introduce new currencies with lower purity. This process gradually led to the devaluation of the currency and a loss of confidence among foreign merchants.

One of the most significant reforms was introduced in the 12th century by Emperor Alexios I Comnenus, who created the hyperpyron, a new gold coin intended to replace the devalued solidus. Although the hyperpyron maintained a good initial purity, it failed to completely stabilize the imperial economy, as financial difficulties continued to increase.

Another devastating blow to Byzantine coinage was the sack of Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade. The crusaders, instead of continuing on to the Holy Land, besieged and sacked the Byzantine capital, devastating its riches and destroying part of the imperial mints. After this event, the production of gold coins suffered a drastic decline and international trade began to prefer other more stable currencies, such as the Florentine florin or the Venetian ducat.

With the restoration of the Empire under the Palaeologus dynasty in 1261, there were timid attempts at economic and monetary revival, but the Empire’s resources were now reduced. The continuous loss of territories, economic isolation and the emergence of new powers such as the Ottoman Empire led the Byzantine Empire to a slow but inexorable decline.

The last Byzantine coins, minted in the decades before the fall of Constantinople in 1453, were of inferior quality to those of previous centuries and now circulated only in local markets. Gold, once a symbol of power and stability, became increasingly rare in the imperial coffers, giving way to low-value copper and silver coins.

The decline of Byzantine coinage was not only the end of a centuries-old economic system, but also marked the closing of a fundamental chapter in the history of numismatics. With the fall of the Empire, Byzantine coins ceased to be minted, but their influence lives on in European mints and in modern collectors, fascinated by their thousand-year history.

#7. The legacy of Byzantine coins

Despite the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, its gold coins continued to exert a profound and lasting influence on the modern world. The economic stability and quality of Byzantine coins have left an indelible mark on the history of numismatics, influencing subsequent monetary systems and fascinating collectors and scholars around the world.

One of the most notable aspects of the Byzantine legacy is the spread of the concept of a stable and internationally recognized currency. The Byzantine solidus remained the benchmark for commercial transactions in the Mediterranean and beyond for centuries, serving as a model for numerous medieval European currencies, including the Florentine florin and the Venetian ducat. These coins adopted many of the solidus’s characteristics, such as the high purity of the gold and religious symbolism, cementing the idea of a strong and reliable currency.

In the artistic and cultural spheres, Byzantine coins influenced the monetary iconography of several subsequent kingdoms and empires. Depictions of Christ Pantocrator, the Virgin Mary and emperors continued to be used in the following centuries, especially in the coins of the Balkans, Russia and the Christian states of the East.

Today, Byzantine gold coins represent one of the most sought-after sectors in numismatic collecting. Their rarity, combined with their historical and artistic value, make them objects of great prestige at international auctions and in private collections. Each specimen tells a unique story: the life of an emperor, the military victories, the economic changes and the religious challenges of an Empire that shaped European and Mediterranean history.

Furthermore, Byzantine coins are valuable sources for scholars. Through the analysis of materials, minting techniques and inscriptions, historians are able to reconstruct political events, economic fluctuations and social dynamics of the time. Every detail, from weight to gold quality, offers clues to the historical context in which the coin was minted.

Finally, the influence of Byzantine coins is not limited to the numismatic sphere. The concept of money as a symbol of power and faith, developed by the Byzantine Empire, has permeated the medieval and modern economy, leaving an indelible mark on the way we perceive money and its value.

Byzantine gold coins are therefore not simple fragments of history: they are tangible testimonies of an Empire that, although disappeared centuries ago, continues to live through the gold it minted and the stories it left as a legacy.

Leave a Reply